May 8, 2023 - CO, UT, WY

As of May 1, snow-water equivalent (SWE) values remain above to much-above normal for the majority of the region, especially in Utah. April precipitation and temperatures were below to much-below normal for the region. Streamflow volume forecasts are above to much-above average for the Upper Colorado River and Great Basins, and the inflow forecast for Lake Powell is 172% of average, continuing to provide much-needed water after record-low water levels. Regional drought conditions significantly improved during April and now drought covers only 32% of the region, driven by wetter conditions in Utah. Neutral ENSO conditions are expected to persist throughout the spring, and there is an increased probability of above average temperatures for parts of Utah and Wyoming during May, and parts of Utah and Colorado from May-July.

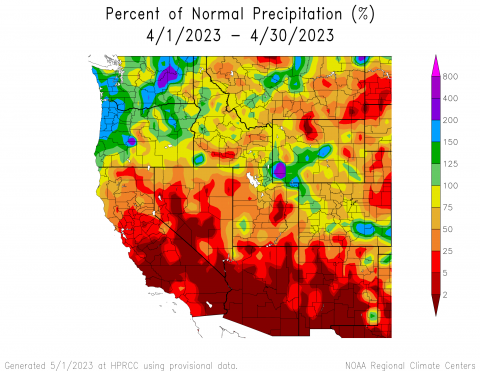

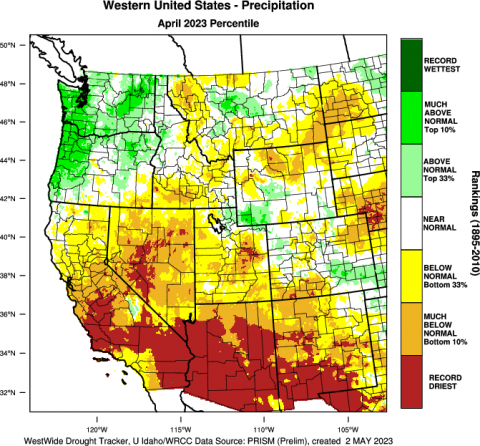

April precipitation was below normal for much of the region. Less than 50% of normal April precipitation occurred in northern Wyoming, particularly in Big Horn County, eastern Utah, particularly in Carbon and Emery Counties, and northeastern Colorado. Record-dry conditions occurred in east-central Utah, mostly in Carbon County. Areas of above normal precipitation occurred in southwestern to central Wyoming from the Upper Green River to western North Platte Basins, and southeastern Colorado along the Arkansas River Basin. An area of much-above normal precipitation occurred in Lincoln and Uinta Counties in southwestern Wyoming.

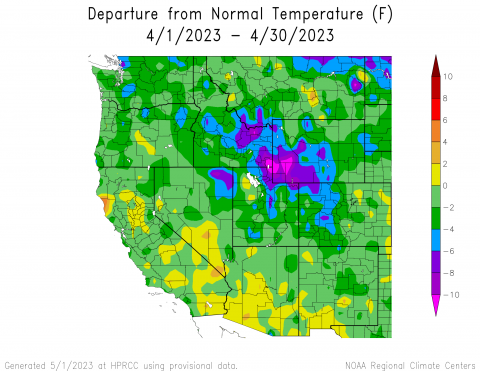

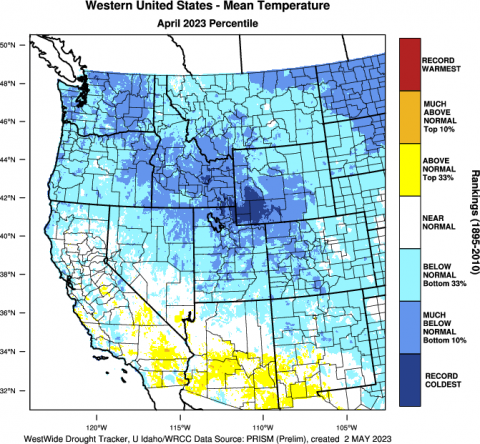

Regional temperatures during April were below normal. Large portions of Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming experienced much-below normal temperatures, particularly in Wyoming where temperatures were 6 to 10 degrees below normal. Record-cold temperatures for April occurred in the Upper Green River region of southwestern Wyoming and northernmost Utah, mostly in Rich County.

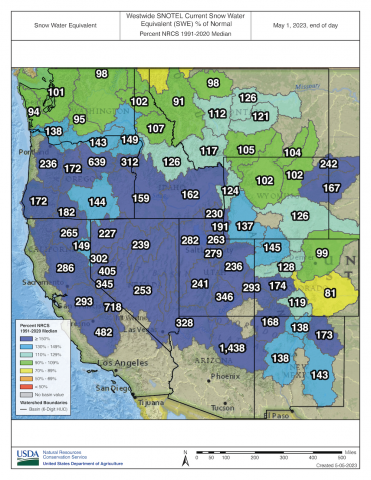

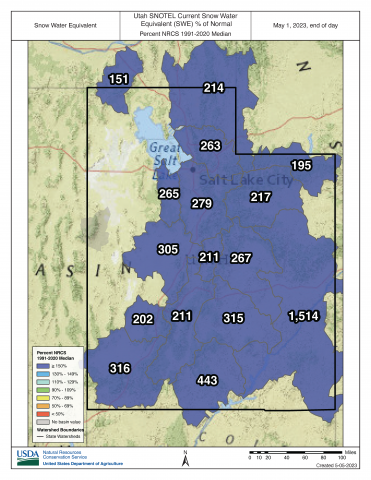

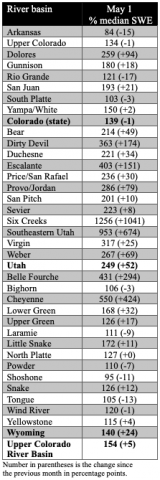

Regional snowpack is near to much-above normal for the entire region except for the Arkansas River Basin where May 1 SWE is slightly below normal at 81%. Much-above normal SWE exists for much of the region, including northeastern Wyoming, southwestern Colorado, and all of Utah, with a staggering 1,256% of normal SWE for the Six Creeks Basin on the Wasatch Front and 953% of normal SWE for the Southeastern Utah Basin. Extremely high percent normal SWE is driven by continued deep snowpack at low elevation sites. For example, the Louis Meadows SNOTEL site (6,700 feet) in the Six Creeks Basin is at 9,933% of normal because May 1 median SWE is 0.3” and current SWE is 29.8”. Statewide percent median SWE was 139% for Colorado, 249% for Utah, and 140% for Wyoming. As of May 1, snowpack is generally near normal east of the Continental Divide in Colorado and in northern Wyoming, and above normal on the West Slope of Colorado and in southern Wyoming.

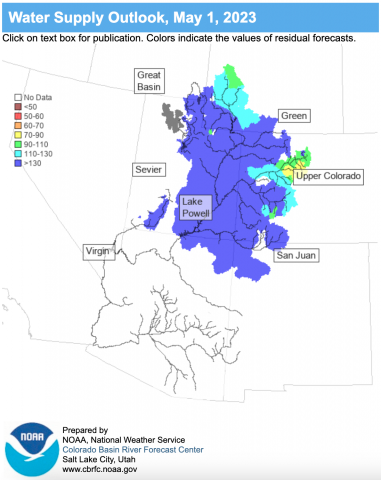

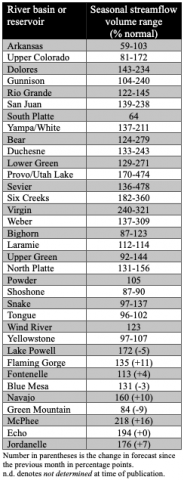

Seasonal streamflow volume forecasts are above average to much-above average for most regional river basins. Streamflow forecasts are highest for the Great Basin where forecasted volumes are 132-451% of average. Below normal (60-90%) seasonal streamflow volumes are forecasted for the South Platte and Arkansas Basins, and near-normal (90-110%) volumes are forecasted for the Big Horn, Powder, Snake, Upper Colorado (mainstem), and Yellowstone River Basins. Above normal seasonal streamflow (110-130%) is forecasted for the Rio Grande and Upper Green River Basins, and much-above normal streamflow (>130%) is forecasted for the remaining regional river basins, with streamflow forecasts reaching above 300% for sites in the Provo/Utah Lake, Sevier, Six Creeks, Virgin, and Weber River Basins. Seasonal streamflow forecasts for most large Upper Colorado River Basin reservoirs are much-above normal, leaving only Fontenelle with an above normal forecast of 113% and Green Mountain with a below normal forecast of 84%. The inflow forecast for Lake Powell is 172% of normal.

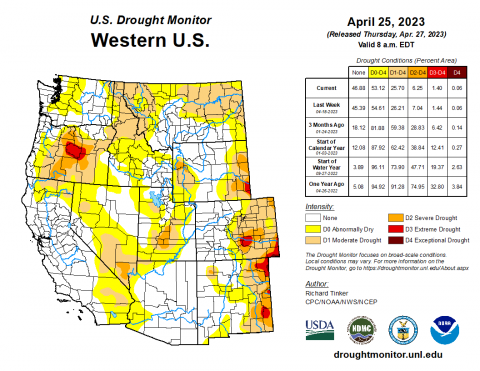

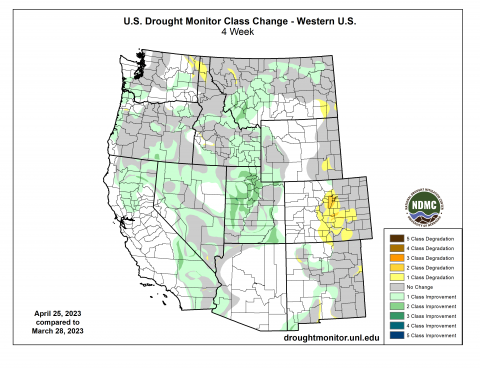

Regional drought conditions were mixed, with improvement throughout most of Utah and degradation throughout the Front Range and south-central portion of Colorado. At the end of April, drought covered 32% of the Intermountain West, down from 45% at the end of March. Drought conditions significantly improved in Utah; drought covered 65% of the state at the end of March, decreasing to 19% at the end of April. Drought conditions slightly improved in Wyoming, from 37% to 30% coverage by the end of April. Drought conditions worsened in Colorado, increasing in coverage from 36% to 44% by the end of April. Pockets of extreme (D3) drought remain in southeastern Wyoming and Colorado and developed in south-central Colorado. Exceptional (D4) drought continues in southeastern Colorado’s Baca County.

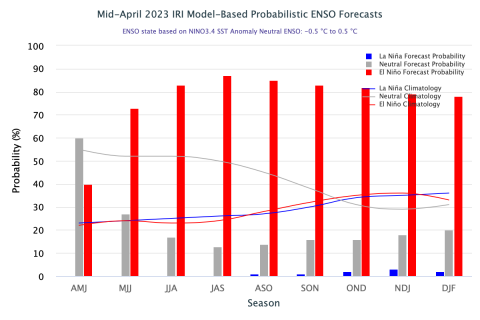

Neutral ENSO conditions continued in April and are expected throughout the spring. In some regions of the Pacific Ocean, sea surface temperatures warmed to above average, indicating a shift towards El Niño in the coming months. There is a 62% chance of El Niño developing during May-July, and a greater than 80% chance of El Niño by the fall. There is an increased probability of above normal temperatures during May in western Wyoming and northern Utah. The May-July NOAA seasonal forecasts predict an increased probability of above normal temperatures in southeastern Utah and southern Colorado.

Significant April weather event. Little Cottonwood Canyon (LCC) experienced a historic avalanche cycle in early April caused by historically deep snowpack (903” of snowfall at Alta), intense snowfall, and rapid warming. From 4/3 - 4/5, upper LCC received 63” of snow with 4.5” of SWE. Temperatures were very cold during the storm, including a record minimum temperature at the Alta Guard site of 1F on 4/6. By 4/10, the maximum temperature warmed to 56F, a daily record. A daily record temperature of 56F was also set on 4/11 and concluded a full three days without below freezing temperatures, which increases the risk for wet slab avalanches.

High snowfall and warm temperatures caused very dangerous avalanche conditions, resulting in the closure of LCC Road from 4/2 - 4/13 with a brief opening on the morning of 4/7 to allow people to leave the canyon. The length of this canyon closure is unprecedented. Two distinct avalanche cycles occurred during the 12-day canyon closure. The first avalanche cycle occurred during and immediately after the storm. The second avalanche cycle was a wet avalanche cycle that began around 4/9 and was caused by rapidly warming temperatures and the lack of below freezing conditions at night. Many dozens of avalanches occurred naturally or as a result of avalanche mitigation efforts in avalanche paths that impact the road or infrastructure in LCC. Avalanches buried the road in 15-20 locations up to 30 feet deep and several hundred yards wide. Some paths hit the road multiple times. Many avalanche paths that ran have a historical avalanche frequency of more than 50 years and these paths enlarged their run-out zones, mowing down mature aspen, fir, and oak trees. One path, Coalpit #4, ran so large that the avalanche crossed Little Cottonwood Creek and traveled upslope to hit the road. Another slide occurred on 4/6 where a slide path across the road from Snowbird slid naturally and buried the edge of the beginner ski slope while the ski area was open. Snowbird immediately closed the resort and performed a probe line search of the area to ensure no one was buried. Fortunately, no one was injured in the incident.